Haystack's Pipeline - a deep dive

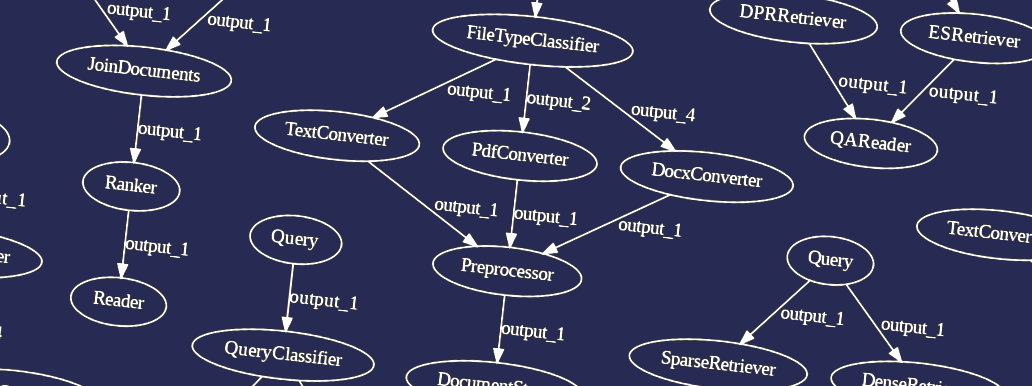

Building and breaking Haystack's Pipelines to show where they shine and where they fail.

October 15, 2023If you’ve ever looked at Haystack before, you must have come across the concept of Pipeline, one of the most prominent concepts of the framework. However, this abstraction is by no means an obvious choice when it comes to NLP libraries. Why did we adopt this concept, and what does it bring us?

In this post, I go into all the details of how the Pipeline abstraction works in Haystack now, why it works this way, and its strengths and weaknesses. This deep dive into the current state of the framework is also a premise for the next episode, where I will explain how Haystack 2.0 addresses this version’s shortcomings.

If you think you already know how Haystack Pipelines work, give this post a chance: I might mWanage to change your mind.

A Bit Of History

Interestingly, in the very first releases of Haystack, Pipelines were not a thing. Version 0.1.0 was released with a simpler object, the Finder, that did little more than gluing together a Retriever and a Reader, the two fundamental building blocks of a semantic search application.

In the next few months, however, the capabilities of language models expanded to enable many more use cases. One hot topic was hybrid retrieval: a system composed of two different Retrievers, an optional Ranker, and an optional Reader. This kind of application clearly didn’t fit the Finder’s design, so in version 0.6.0 the Pipeline object was introduced: a new abstraction that helped users build applications as a graph of components.

Pipeline’s API was a huge step forward from Finder. It instantly enabled seemingly endless combinations of components, unlocked almost all use cases conceivable, and became a foundational Haystack concept meant to stay for a very long time. In fact, the API offered by the first version of Pipeline changed very little since its initial release.

This is the snippet included in the release notes of version 0.6.0 to showcase hybrid retrieval. Does it look familiar?

p = Pipeline()

p.add_node(component=es_retriever, name="ESRetriever", inputs=["Query"])

p.add_node(component=dpr_retriever, name="DPRRetriever", inputs=["Query"])

p.add_node(component=JoinDocuments(join_mode="concatenate"), name="JoinResults", inputs=["ESRetriever", "DPRRetriever"])

p.add_node(component=reader, name="QAReader", inputs=["JoinResults"])

res = p.run(query="What did Einstein work on?", top_k_retriever=1)

A Powerful Abstraction

One fascinating aspect of this Pipeline model is the simplicity of its user-facing API. In almost all examples, you see only two or three methods used:

add_node: to add a component to the graph and connect it to the others.run: to run the Pipeline from start to finish.draw: to draw the graph of the Pipeline to an image.

At this level, users don’t need to know what kind of data the components need to function, what they produce, or even what the components do: all they need to know is the place they must occupy in the graph for the system to work.

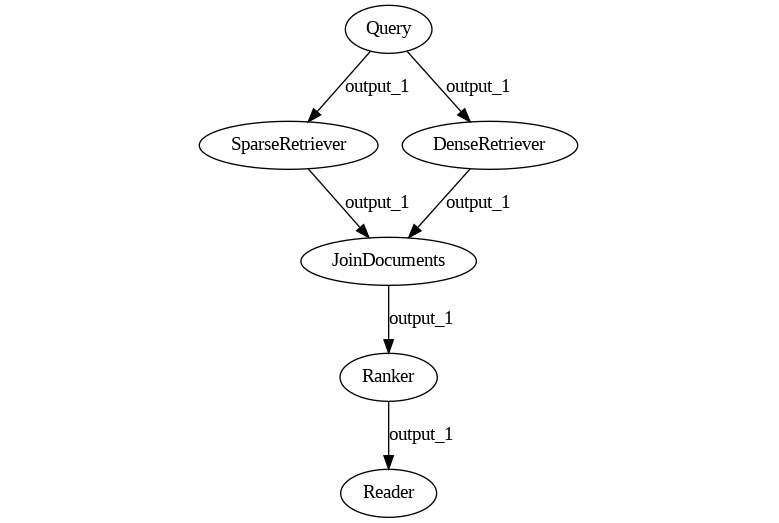

For example, as long as the users know that their hybrid retrieval pipeline should look more or less like this (note: this is the output of Pipeline.draw()), translating it into a Haystack Pipeline object using a few add_node calls is mostly straightforward.

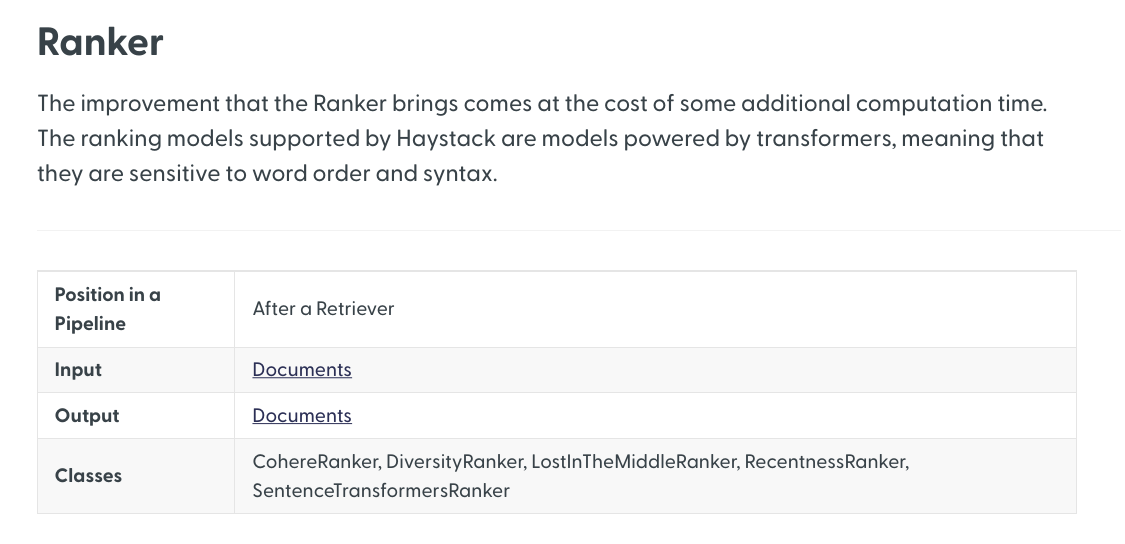

This fact is reflected by the documentation of the various components as well. For example, this is how the documentation page for Ranker opens:

Note how the first information about this component is where to place it. Right after, it specifies its inputs and outputs, even though it’s not immediately clear why we need this information, and then lists which specific classes can cover the role of a Ranker.

The message is clear: all Ranker classes are functionally interchangeable, and as long as you place them correctly in the Pipeline, they will fulfill the function of Ranker as you expect them to. Users don’t need to understand what distinguishes CohereRanker from RecentnessReranker unless they want to: the documentation promises that you can swap them safely, and thanks to the Pipeline abstraction, this statement mostly holds true.

Ready-made Pipelines

But how can the users know which sort of graph they have to build?

Most NLP applications are made by a relatively limited number of high-level components: Retriever, Readers, Rankers, plus the occasional Classifier, Translator, or Summarizer. Systems requiring something more than these components used to be really rare, at least when talking about “query” pipelines (more on this later).

Therefore, at this level of abstraction, there are just a few graph topologies possible. Better yet, they could each be mapped to high-level use cases such as semantic search, language-agnostic document search, hybrid retrieval, and so on.

But the crucial point is that, in most cases, tailoring the application did not require any changes to the graph’s shape. Users only need to identify their use case, find an example or a tutorial defining the shape of the Pipeline they need, and then swap the single components with other instances from the same category until they find the best combination for their exact requirements.

This workflow was evident and encouraged: it was the philosophy behind Finder as well, and from version 0.6.0, Haystack immediately provided what are called “ Ready-made Pipelines”: objects that initialized the graph on the user’s behalf, and expected as input the components to place in each point of the graph: for example a Reader and a Retriever, in case of simple Extractive QA.

With this further abstraction on top of Pipeline, creating an NLP application became an action that doesn’t even require the user to be aware of the existence of the graph. In fact:

pipeline = ExtractiveQAPipeline(reader, retriever)

is enough to get your Extractive QA applications ready to answer your questions. And you can do so with just another line.

answers = Pipeline.run(query="What did Einstein work on?")

“Flexibility powered by DAGs”

This abstraction is extremely powerful for the use cases that it was designed for. There are a few layers of ease of use vs. customization the user can choose from depending on their expertise, which help them progress from a simple ready-made Pipeline to fully custom graphs.

However, the focus was oriented so much on the initial stages of the user’s journey that power-users’ needs were sometimes forgotten. Such issues didn’t show immediately, but quickly added friction as soon as the users tried to customize their system beyond the examples from the tutorials and the documentation.

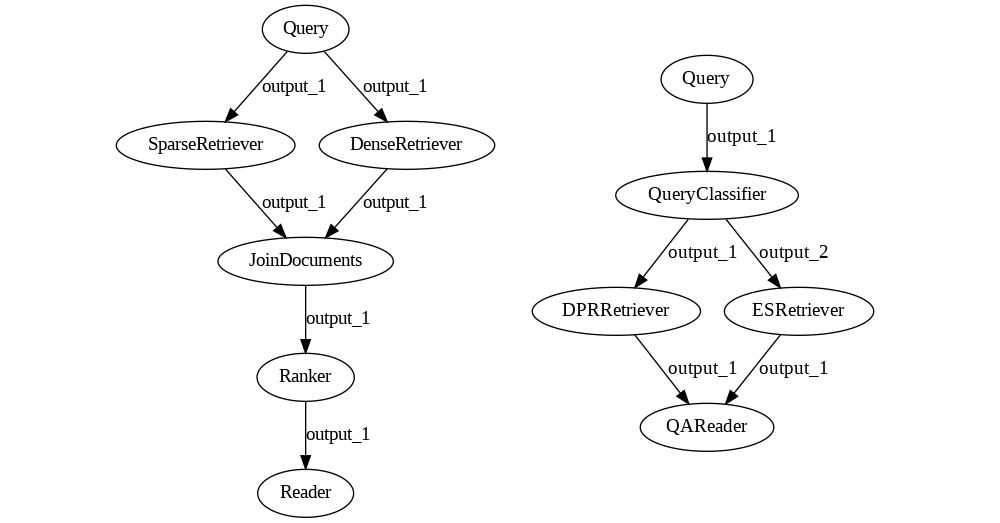

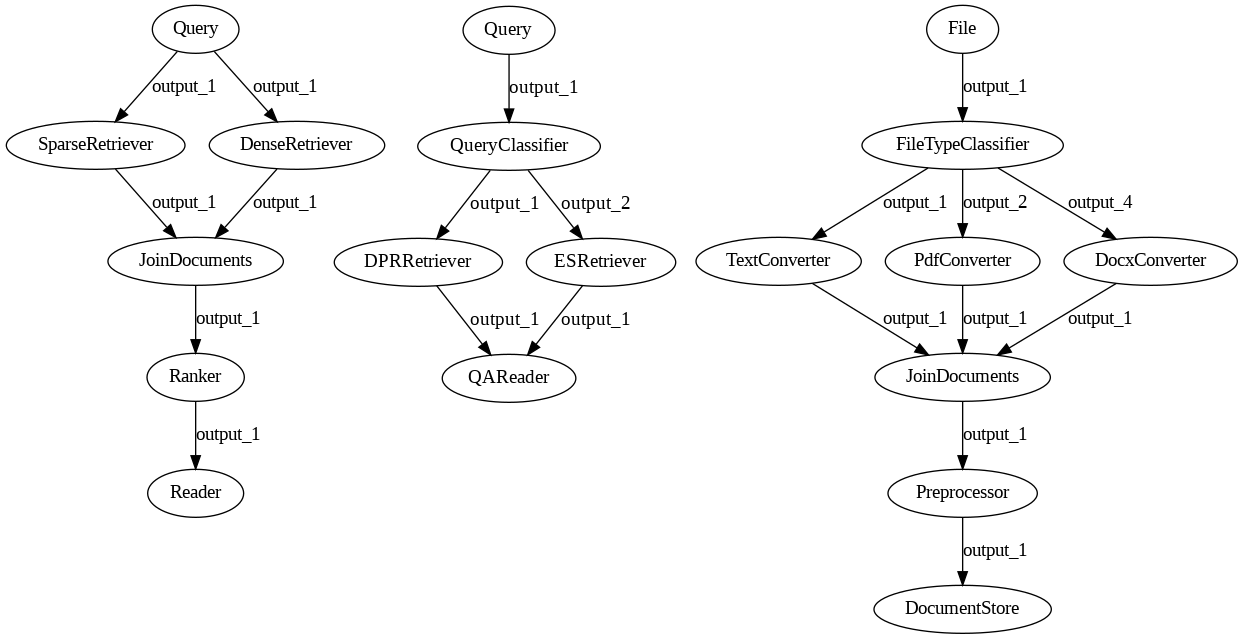

For an example of these issues, let’s talk about pipelines with branches. Here are two small, apparently very similar pipelines.

The first Pipeline represents the Hybrid Retrieval use case we’ve met with before. Here, the Query node sends its outputs to both retrievers, and they both produce some output. For the Reader to make sense of this data, we need a Join node that merges the two lists into one and a Ranker that takes the lists and sorts them again by similarity to the query. Ranker then sends the rearranged list to the Reader.

The second Pipeline instead performs a simpler form of Hybrid Retrieval. Here, the Query node sends its outputs to a Query Classifier, which then triggers only one of the two retrievers, the one that is expected to perform better on it. The triggered Retriever then sends its output directly to the Reader, which doesn’t need to know which Retriever the data comes from. So, in this case, we don’t need the Join node.

The two pipelines are built as you would expect, with a bunch of add_node calls. You can even run them with the same identical code, which is the same code needed for every other Pipeline we’ve seen so far.

pipeline_1 = Pipeline()

pipeline_1.add_node(component=sparse_retriever, name="SparseRetriever", inputs=["Query"])

pipeline_1.add_node(component=dense_retriever, name="DenseRetriever", inputs=["Query"])

pipeline_1.add_node(component=join_documents, name="JoinDocuments", inputs=["SparseRetriever", "DenseRetriever"])

pipeline_1.add_node(component=rerank, name="Ranker", inputs=["JoinDocuments"])

pipeline_1.add_node(component=reader, name="Reader", inputs=["SparseRetriever", "DenseRetriever"])

answers = pipeline_1.run(query="What did Einstein work on?")

pipeline_2 = Pipeline()

pipeline_2.add_node(component=query_classifier, name="QueryClassifier", inputs=["Query"])

pipeline_2.add_node(component=sparse_retriever, name="DPRRetriever", inputs=["QueryClassifier"])

pipeline_2.add_node(component=dense_retriever, name="ESRetriever", inputs=["QueryClassifier"])

pipeline_2.add_node(component=reader, name="Reader", inputs=["SparseRetriever", "DenseRetriever"])

answers = pipeline_2.run(query="What did Einstein work on?")

Both pipelines run as you would expect them to. Hooray! Pipelines can branch and join!

Now, let’s take the first Pipeline and customize it further.

For example, imagine we want to expand language support to include French. The dense Retriever has no issues handling several languages as long as we select a multilingual model; however, the sparse Retriever needs the keywords to match, so we must translate the queries to English to find some relevant documents in our English-only knowledge base.

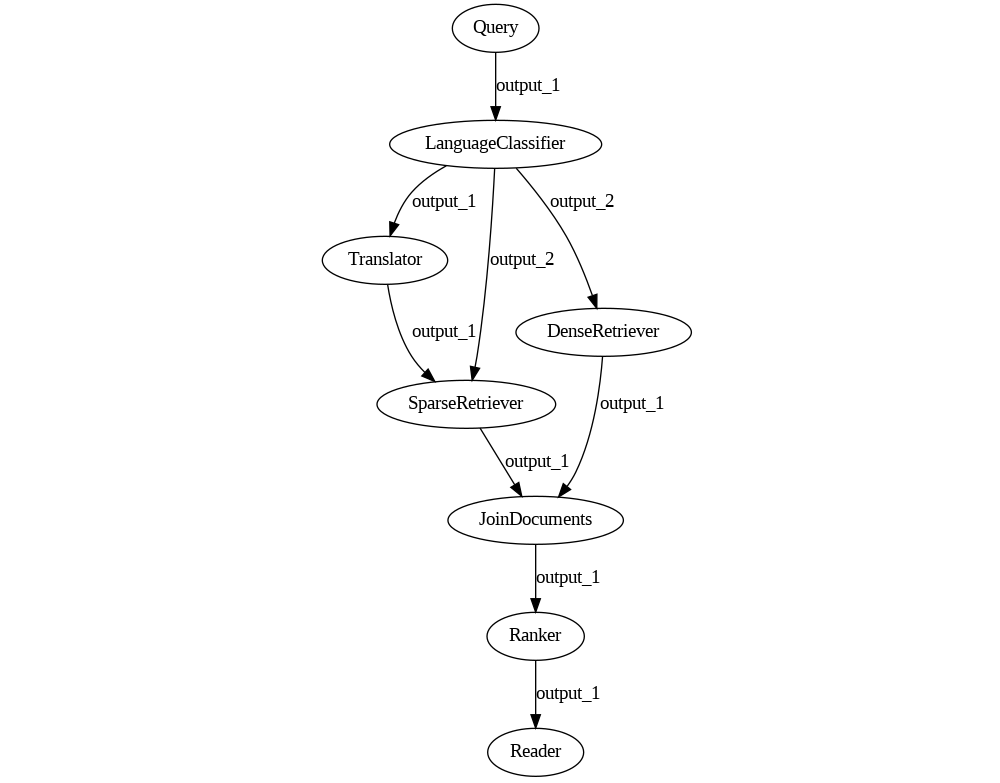

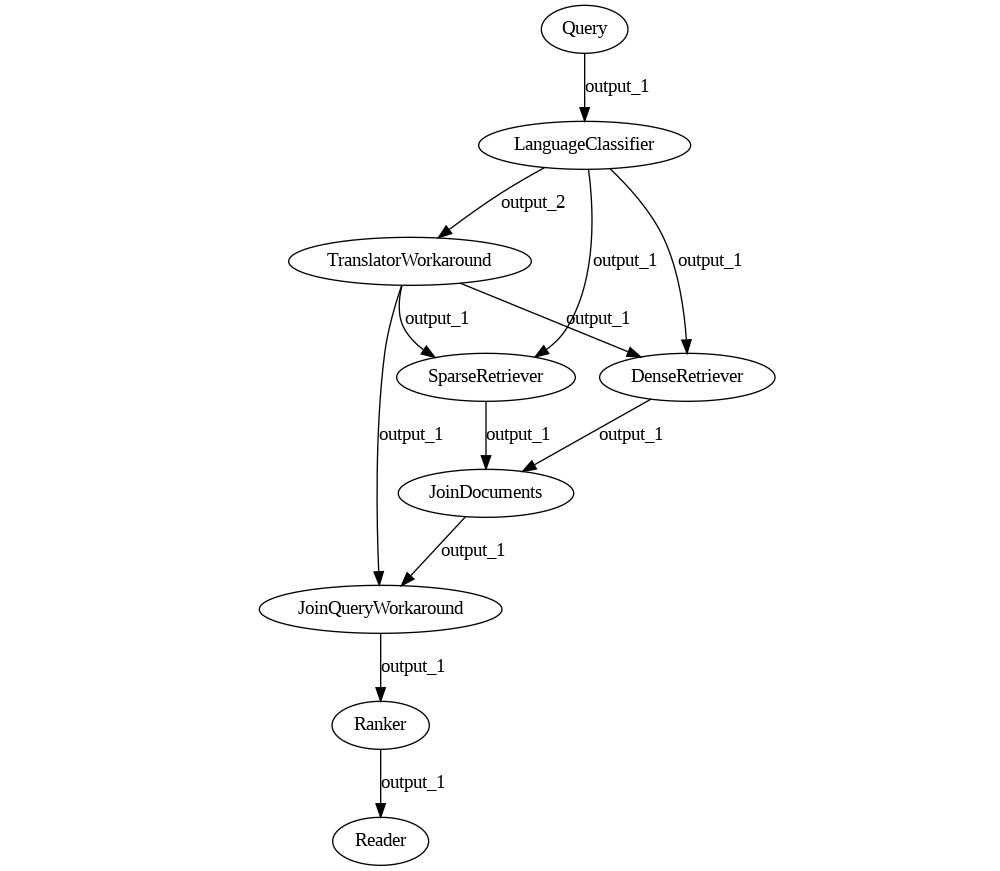

Here is what the Pipeline ends up looking like. Language Classifier sends all French queries over output_1 and all English queries over output_2. In this way, the query passes through the Translator node only if it is written in French.

pipeline = Pipeline()

pipeline.add_node(component=language_classifier, name="LanguageClassifier", inputs=["Query"])

pipeline.add_node(component=translator, name="Translator", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_1"])

pipeline.add_node(component=sparse_retriever, name="SparseRetriever", inputs=["Translator", "LanguageClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=dense_retriever, name="DenseRetriever", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_1", "LanguageClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=join_documents, name="JoinDocuments", inputs=["SparseRetriever", "DenseRetriever"])

pipeline.add_node(component=rerank, name="Ranker", inputs=["JoinDocuments"])

pipeline.add_node(component=reader, name="Reader", inputs=["Ranker"])

But… wait. Let’s look again at the graph and at the code. DenseRetriever should receive two inputs from Language Classifier: both output_1 and output_2, because it can handle both languages. What’s going on? Is this a bug in draw()?

Thanks to the debug=True parameter of Pipeline.run(), we start inspecting what each node saw during the execution, and we realize quickly that our worst fears are true: this is a bug in the Pipeline implementation. The underlying library powering the Pipeline’s graphs takes the definition of Directed Acyclic Graphs very seriously and does not allow two nodes to be connected by more than one edge. There are, of course, other graph classes supporting this case, but Haystack happens to use the wrong one.

Interestingly, Pipeline doesn’t even notice the problem and does not fail. It runs as the drawing suggests: when the query happens to be in French, only the sparse Retriever will process it.

Clearly, this is not good for us.

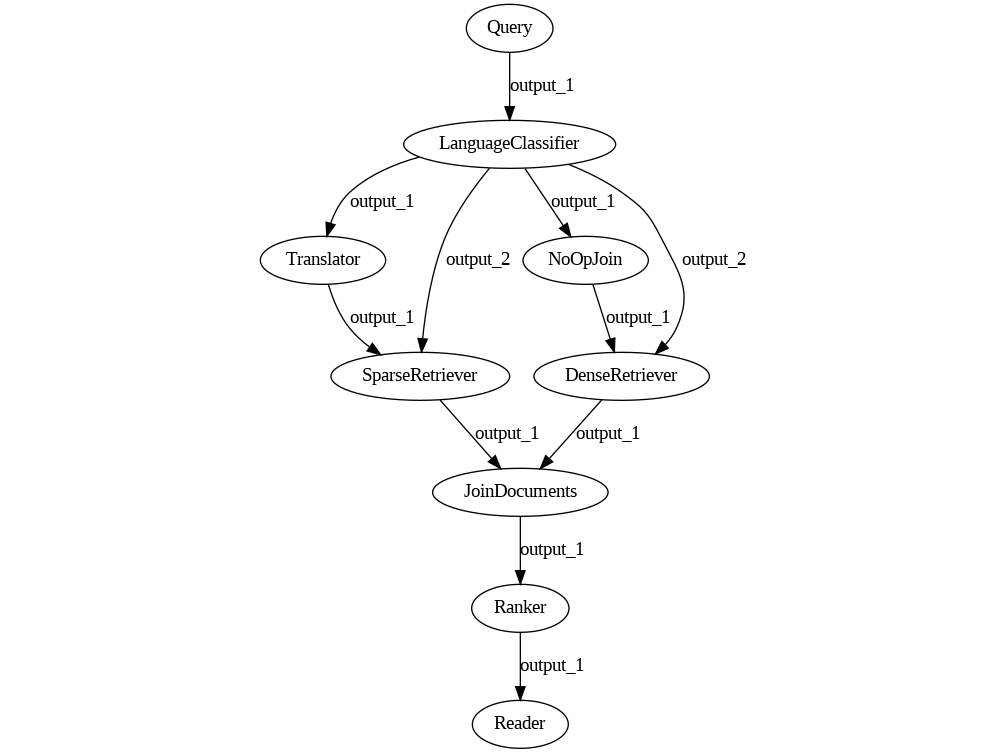

Well, let’s look for a workaround. Given that we’re Haystack power users by now, we realize that we can use a Join node with a single input as a “no-op” node. If we put it along one of the edges, that edge won’t directly connect Language Classifier and Dense Retriever, so the bug should be solved.

So here is our current Pipeline:

pipeline = Pipeline()

pipeline.add_node(component=language_classifier, name="LanguageClassifier", inputs=["Query"])

pipeline.add_node(component=translator, name="Translator", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_1"])

pipeline.add_node(component=sparse_retriever, name="SparseRetriever", inputs=["Translator", "LanguageClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=no_op_join, name="NoOpJoin", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_1"])

pipeline.add_node(component=dense_retriever, name="DenseRetriever", inputs=["NoOpJoin", "LanguageClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=join_documents, name="JoinDocuments", inputs=["SparseRetriever", "DenseRetriever"])

pipeline.add_node(component=rerank, name="Ranker", inputs=["JoinDocuments"])

pipeline.add_node(component=reader, name="Reader", inputs=["Ranker"])

Great news: the Pipeline now runs as we expect! However, when we run a French query, the results are better but still surprisingly bad.

What now? Is the dense Retriever still not running? Is the Translation node doing a poor job?

Some debugging later, we realize that the Translator is amazingly good and the Retrievers are both running. But we forgot another piece of the puzzle: Ranker needs the query to be in the same language as the documents. It requires the English version of the query, just like the sparse Retriever does. However, right now, it receives the original French query, and that’s the reason for the lack of performance. We soon realize that this is very important also for the Reader.

So… how does the Pipeline pass the query down to the Ranker?

Until this point, we didn’t need to know how exactly values are passed from one component to the next. We didn’t need to care about their inputs and outputs at all: Pipeline was doing all this dirty work for us. Suddenly, we need to tell the Pipeline which query to pass to the Ranker and we have no idea how to do that.

Worse yet. There is no way to reliably do that. The documentation seems to blissfully ignore the topic, docstrings give us no pointers, and looking at the routing code of Pipeline we quickly get dizzy and cut the chase. We dig through the Pipeline API several times until we’re confident that there’s nothing that can help.

Well, there must be at least some workaround. Maybe we can forget about this issue by rearranging the nodes.

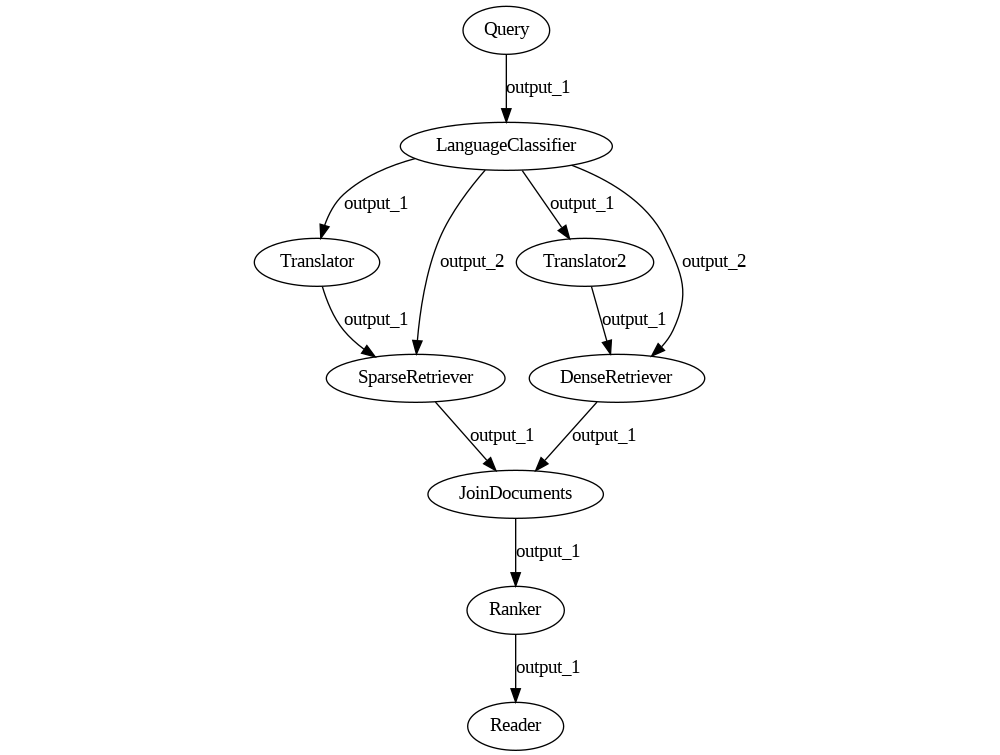

One easy way out is to translate the query for both retrievers instead of only for the sparse one. This solution also eliminates the NoOpJoin node we introduced earlier, so it doesn’t sound too bad.

The Pipeline looks like this now.

pipeline = Pipeline()

pipeline.add_node(component=language_classifier, name="LanguageClassifier", inputs=["Query"])

pipeline.add_node(component=translator, name="Translator", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_1"])

pipeline.add_node(component=sparse_retriever, name="SparseRetriever", inputs=["Translator", "LanguageClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=translator_2, name="Translator2", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_1"])

pipeline.add_node(component=dense_retriever, name="DenseRetriever", inputs=["Translator2", "LanguageClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=join_documents, name="JoinDocuments", inputs=["SparseRetriever", "DenseRetriever"])

pipeline.add_node(component=rerank, name="Ranker", inputs=["JoinDocuments"])

pipeline.add_node(component=reader, name="Reader", inputs=["Ranker"])

We now have two nodes that contain identical translator components. Given that they are stateless, we can surely place the same instance in both places, with different names, and avoid doubling its memory footprint just to work around a couple of Pipeline bugs. After all, Translator nodes use relatively heavy models for machine translation.

This is what Pipeline replies as soon as we try.

PipelineConfigError: Cannot add node 'Translator2'. You have already added the same

instance to the Pipeline under the name 'Translator'.

Okay, so it seems like we can’t re-use components in two places: there is an explicit check against this, for some reason. Alright, let’s rearrange again this Pipeline with this new constraint in mind.

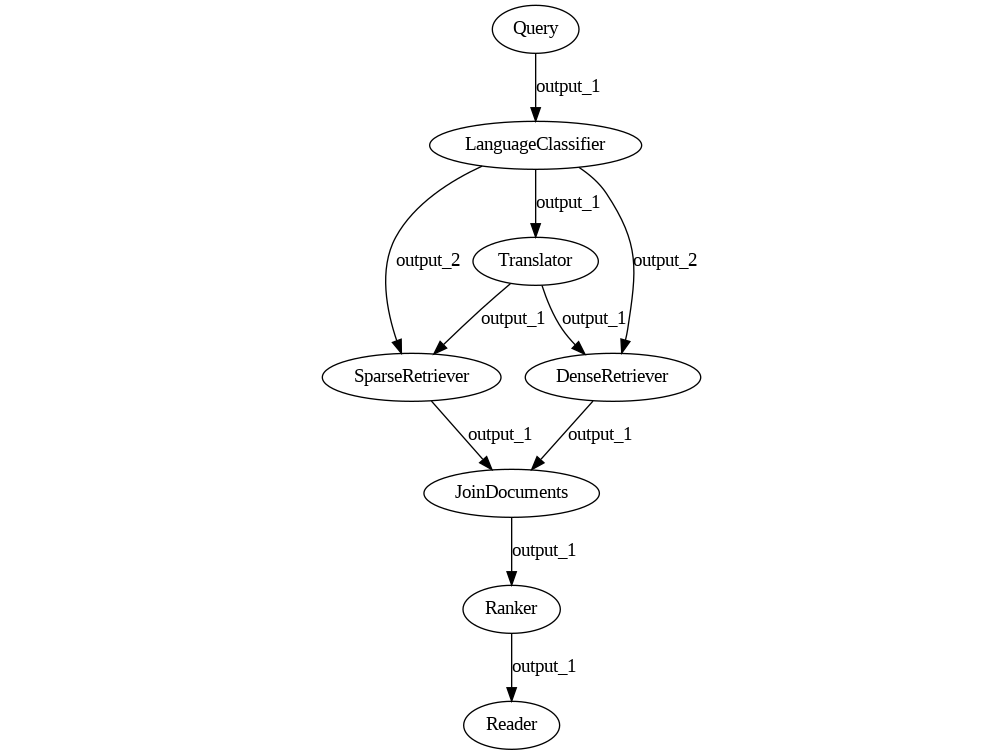

How about we first translate the query and then distribute it?

pipeline = Pipeline()

pipeline.add_node(component=language_classifier, name="LanguageClassifier", inputs=["Query"])

pipeline.add_node(component=translator, name="Translator", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_1"])

pipeline.add_node(component=sparse_retriever, name="SparseRetriever", inputs=["Translator", "LanguageClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=dense_retriever, name="DenseRetriever", inputs=["Translator", "LanguageClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=join_documents, name="JoinDocuments", inputs=["SparseRetriever", "DenseRetriever"])

pipeline.add_node(component=rerank, name="Ranker", inputs=["JoinDocuments"])

pipeline.add_node(component=reader, name="Reader", inputs=["Ranker"])

Looks neat: there is no way now for the original French query to reach Ranker now. Right?

We run the pipeline again and soon realize that nothing has changed. The query received by Ranker is still in French, untranslated. Shuffling the order of the add_node calls and the names of the components in the inputs parameters seems to have no effect on the graph. We even try to connect Translator directly with Ranker in a desperate attempt to forward the correct value, but Pipeline now starts throwing obscure, apparently meaningless error messages like:

BaseRanker.run() missing 1 required positional argument: 'documents'

Isn’t Ranker receiving the documents from JoinDocuments? Where did they go?

Having wasted far too much time on this relatively simple Pipeline, we throw the towel, go to Haystack’s Discord server, and ask for help.

Soon enough, one of the maintainers shows up and promises a workaround ASAP. You’re skeptical at this point, but the workaround, in fact, exists.

It’s just not very pretty.

pipeline = Pipeline()

pipeline.add_node(component=language_classifier, name="LanguageClassifier", inputs=["Query"])

pipeline.add_node(component=translator_workaround, name="TranslatorWorkaround", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=sparse_retriever, name="SparseRetriever", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_1", "TranslatorWorkaround"])

pipeline.add_node(component=dense_retriever, name="DenseRetriever", inputs=["LanguageClassifier.output_1", "TranslatorWorkaround"])

pipeline.add_node(component=join_documents, name="JoinDocuments", inputs=["SparseRetriever", "DenseRetriever"])

pipeline.add_node(component=join_query_workaround, name="JoinQueryWorkaround", inputs=["TranslatorWorkaround", "JoinDocuments"])

pipeline.add_node(component=rerank, name="Ranker", inputs=["JoinQueryWorkaround"])

pipeline.add_node(component=reader, name="Reader", inputs=["Ranker"])

Note that you need two custom nodes: a wrapper for the Translator and a brand-new Join node.

class TranslatorWorkaround(TransformersTranslator):

outgoing_edges = 1

def run(self, query):

results, edge = super().run(query=query)

return {**results, "documents": [] }, "output_1"

def run_batch(self, queries):

pass

class JoinQueryWorkaround(JoinNode):

def run_accumulated(self, inputs, *args, **kwargs):

return {"query": inputs[0].get("query", None), "documents": inputs[1].get("documents", None)}, "output_1"

def run_batch_accumulated(self, inputs):

pass

Along with this beautiful code, we also receive an explanation about how the JoinQueryWorkaround node works only for this specific Pipeline and is pretty hard to generalize, which is why it’s not present in Haystack right now. I’ll spare you the details: you will have an idea why by the end of this journey.

Wanna play with this Pipeline yourself and try to make it work in another way? Check out the Colab or the gist and have fun.

Having learned only that it’s better not to implement unusual branching patterns with Haystack unless you’re ready for a fight, let’s now turn to the indexing side of your application. We’ll stick to the basics this time.

Indexing Pipelines

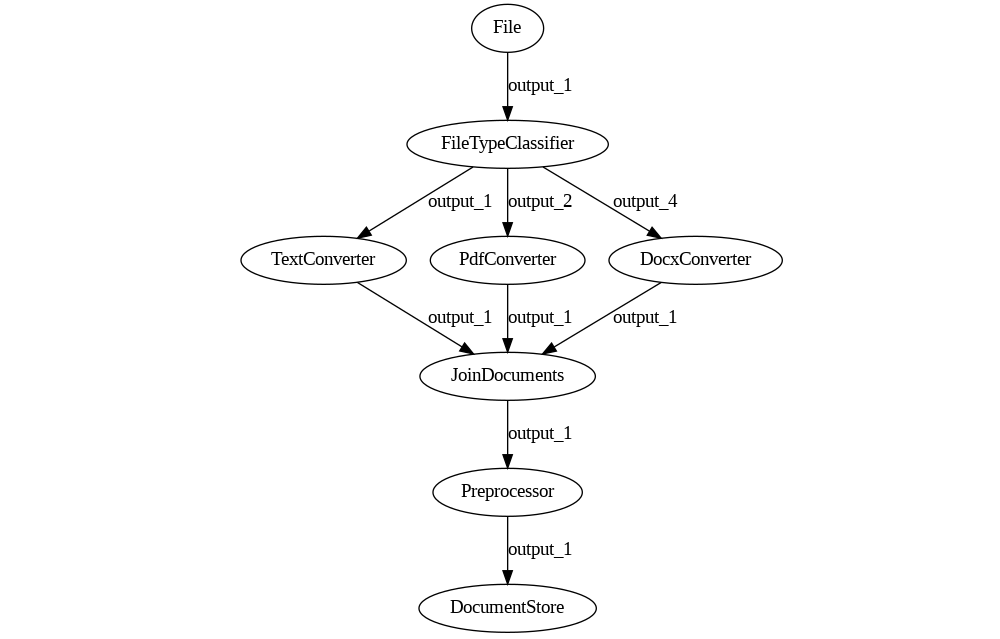

Indexing pipelines’ main goal is to transform files into Documents from which a query pipeline can later retrieve information. They mostly look like the following.

And the code looks just like how you would expect it.

pipeline = Pipeline()

pipeline.add_node(component=file_type_classifier, name="FileTypeClassifier", inputs=["File"])

pipeline.add_node(component=text_converter, name="TextConverter", inputs=["FileTypeClassifier.output_1"])

pipeline.add_node(component=pdf_converter, name="PdfConverter", inputs=["FileTypeClassifier.output_2"])

pipeline.add_node(component=docx_converter, name="DocxConverter", inputs=["FileTypeClassifier.output_4"])

pipeline.add_node(component=join_documents, name="JoinDocuments", inputs=["TextConverter", "PdfConverter", "DocxConverter"])

pipeline.add_node(component=preprocessor, name="Preprocessor", inputs=["JoinDocuments"])

pipeline.add_node(component=document_store, name="DocumentStore", inputs=["Preprocessor"])

pipeline.run(file_paths=paths)

There is no surprising stuff here. The starting node is File instead of Query, which seems logical given that this Pipeline expects a list of files, not a query. There is a document store at the end which we didn’t use in query pipelines so far, but it’s not looking too strange. It’s all quite intuitive.

Indexing pipelines are run by giving them the paths of the files to convert. In this scenario, more than one Converter may run, so we place a Join node before the PreProcessor to make sense of the merge. We make sure that the directory contains only files that we can convert, in this case, .txt, .pdf, and .docx, and then we run the code above.

The code, however, fails.

ValueError: Multiple non-default file types are not allowed at once.

The more we look at the error, the less it makes sense. What are non-default file types? Why are they not allowed at once, and what can I do to fix that?

We head for the documentation, where we find a lead.

So it seems like the File Classifier can only process the files if they’re all of the same type.

After all we’ve been through with the Hybrid Retrieval pipelines, this sounds wrong. We know that Pipeline can run two branches at the same time. We’ve been doing it all the time just a moment ago. Why can’t FileTypeClassifier send data to two converters just like LanguageClassifier sends data to two retrievers?

Turns out, this is not the same thing.

Let’s compare the three pipelines and try to spot the difference.

In the first case, Query sends the same identical value to both Retrievers. So, from the component’s perspective, there’s a single output being produced: the Pipeline takes care of copying it for all nodes connected to it.

In the second case, QueryClassifier can send the query to either Retriever but never to both. So, the component can produce two different outputs, but at every run, it will always return just one.

In the third case, FileTypeClassifier may need to produce two different outputs simultaneously: for example, one with a list of text files and one with a list of PDFs. And it turns out this can’t be done. This is, unfortunately, a well-known limitation of the Pipeline/BaseComponent API design.

The output of a component is defined as a tuple, (output_values, output_edge), and nodes can’t produce a list of these tuples to send different values to different nodes.

That’s the end of the story. This time, there is no workaround. You must pass the files individually or forget about using a Pipeline for this task.

Validation

On top of these challenges, other tradeoffs had to be taken for the API to look so simple at first impact. One of these is connection validation.

Let’s imagine we quickly skimmed through a tutorial and got one bit of information wrong: we mistakenly believe that in an Extractive QA Pipeline, you need to place a Reader in front of a Retriever. So we sit down and write this.

p = Pipeline()

p.add_node(component=reader, name="Reader", inputs=["Query"])

p.add_node(component=retriever, name="Retriever", inputs=["Reader"])

Up to this point, running the script raises no error. Haystack is happy to connect these two components in this order. You can even draw() this Pipeline just fine.

Alright, so what happens when we run it?

res = p.run(query="What did Einstein work on?")

BaseReader.run() missing 1 required positional argument: 'documents'

This is the same error we’ve seen in the translating hybrid retrieval pipeline earlier, but fear not! Here, we can follow the suggestion of the error message by doing:

res = p.run(query="What did Einstein work on?", documents=document_store.get_all_documents())

And to our surprise, this Pipeline doesn’t crash. It just hangs there, showing an insanely slow progress bar, telling us that some inference is in progress. A few hours later, we kill the process and consider switching to another framework because this one is clearly very slow.

What happened?

The cause of this issue is the same that makes connecting Haystack components in a Pipeline so effortless, and it’s related to the way components and Pipeline communicate. If you check Pipeline.run()’s signature, you’ll see that it looks like this:

def run(

self,

query: Optional[str] = None,

file_paths: Optional[List[str]] = None,

labels: Optional[MultiLabel] = None,

documents: Optional[List[Document]] = None,

meta: Optional[Union[dict, List[dict]]] = None,

params: Optional[dict] = None,

debug: Optional[bool] = None,

):

which mirrors the BaseComponent.run() signature, the base class nodes have to inherit from.

@abstractmethod

def run(

self,

query: Optional[str] = None,

file_paths: Optional[List[str]] = None,

labels: Optional[MultiLabel] = None,

documents: Optional[List[Document]] = None,

meta: Optional[dict] = None,

) -> Tuple[Dict, str]:

This match means a few things:

-

Every component can be connected to every other because their inputs are identical.

-

Every component can only output the same variables received as input.

-

It’s impossible to tell if it makes sense to connect two components because their inputs and outputs always match.

Take this with a grain of salt: the actual implementation is far more nuanced than what I just showed you, but the problem is fundamentally this: components are trying to be as compatible as possible with all others and they have no way to signal, to the Pipeline or to the users, that they’re meant to be connected only to some nodes and not to others.

In addition to this problem, to respect the shared signature, components often take inputs that they don’t use. A Ranker only needs documents, so all the other inputs required by the run method signature go unused. What do components do with the values? It depends:

- Some have them in the signature and forward them unchanged.

- Some have them in the signature and don’t forward them.

- Some don’t have them in the signature, breaking the inheritance pattern, and Pipeline reacts by assuming that they should be added unchanged to the output dictionary.

If you check closely the two workaround nodes for the Hybrid Retrieval pipeline we tried to build before, you’ll notice the fix entirely focuses on altering the routing of the unused parameters query and documents to make the Pipeline behave the way the user expects. However, this behavior does not generalize: a different pipeline would require another behavior, which is why the components behave differently in the first place.

Wrapping up

I could go on for ages talking about the shortcomings of complex Pipelines, but I’d rather stop here.

Along this journey into the guts of Haystack Pipelines, we’ve seen at the same time some beautiful APIs and the ugly consequences of their implementation. As always, there’s no free lunch: trying to over-simplify the interface will bite back as soon as the use cases become nontrivial.

However, we believe that this concept has a huge potential and that this version of Pipeline can be improved a lot before the impact on the API becomes too heavy. In Haystack 2.0, armed with the experience we gained working with this implementation of Pipeline, we reimplemented it in a fundamentally different way, which will prevent many of these issues.

In the next post, we’re going to see how.